Apart from tricks and kicks – brief discussion on key moves in art criticism

Text/Vivian Ting

Here comes the golden age for artworks. The booming art market does not only rejuvenate the public’s imagination towards art itself, but also renovate the cityscape – with the joint efforts from the Government, cultural institutions and business sector alike, art decorations are seen in government buildings, markets, parks, and shopping centres. You may have an art piece as your “neighbour” when you are on public transport. This cultural shift in the territory brings various artistic writings – news reports on art events, features in magazines, exhibition catalogues, and commentaries on the Internet etc. While contemporary art sparks off wide ranges of creative practices, artistic writings complete the picture with words.

Artistic writings to this day, which are collectively termed as “art criticism”, carry diverse components – ranging from personal reflections, intellectual packaging from commercial art galleries, analysis of the art market, to aesthetic account on artists and their works. One key trick employed in giving art criticism is to replace what one sees and experiences with what one emotionally connects. The other one is to attach academic theories and cultural criticism to whatever art pieces in description. The tricks extend neither the space for art criticism nor discussions on the development in art, culture and social ideology. Instead, they only bring vague and detached accounts of art itself.

How are we going to open up new horizons in the field of art criticism? Let’s explore how four local art critics do so through an analysis of their writing styles.

Three, Chan Sai Lok exercises his tricks, “cloud hands”, by first targeting at the presentation of each art piece. He successfully draws readers into the aura of the work for an experience of the artists’ concepts and emotions. Sai Lok’s focus in his art criticism is to elaborate on how artists transform their ineffable emotions, delicate senses and intellectual ideas into friendly art pieces. He does it through detailed analysis on the text and its structure, rhythm, materials and contexts of visual languages. When it comes to contemporary art bearing intellectual messages, Sai Lok explores the links between the challenging presentation and its grounding principles and theories. Sai Lok further demonstrates his writing in a poetic style – by going with the flow of both the visual impacts of the work and his personal emotional shifts viewing it. He vividly expresses feelings in tantalizing words, even when it is an inimical work in description. Plain and loose as his texts may seem, Sai Lok auspiciously delivers his views, offers diverse analytical approaches and poses new questions to readers.

Yang Yeung exercises her meticulous thinking and all-rounded arguments in her art criticism. She first detects flaws in her opponents’ stance by analyzing their logic. When the flaws are exposed and counter-attack is impossible, she readily advances herself with her solid standpoints. Yang sees every artwork as a material representation of physical senses and intellectual thinking. It might be hard to translate the direct emotional strikes it brings to audience into words; yet the humanistic values, critical thinking and genuine feelings that art explores all relate closely to the set of objective rules binding individuals together in a society. Yang’s art criticism aims at starting an ideological debate – in which one shares his logic with the kindred, fuels discussions and reflects on the current cultural context. Her excellence in understanding of various academic theories secures herself a firm foothold in the field. It is with that she organizes her ideas and elaborates on principles and values guiding her journey in art. For Yang, the writing process is one with endless reflections. Her ultimate goal is not to back her ideas with countless theories, but to save positive energy against the negative aura that persists in the contemporary art culture.

Jeff Leung firmly grasps the theme of art criticism. He twists, lingers and support ideas with historical examples. His sole focus on art criticism stays in the way exhibitions create multiple meanings in art. He sees exhibitions as an indisputable platform, not only for showcasing contemporary art, but also for continual discussions among artists, curators and audience. It is through this platform our perception in art can be sustained, constructed and deconstructed. Important as it is, local art criticism seldom touches on the system of curation. Jeff concentrates on examination of the development history of local exhibitions – from types of curation, mechanism and logic driving exhibitions to shifts in their space. From these he considers the construction of tastes in contemporary art and relevant systems. Leung writes freely to detail evolutions in the art ecosystem: borrowing elements from popular culture like animation, creating new syntax by putting nouns in different contexts together. This not only opens up new dimension in readers’ mind, but also reflects how curation impacts audiences’ viewing experience. It is from that unique experience one creates, adds, deletes and alters the meaning and art piece carries.

Seeing herself as a core member of the local art scene, Anthony Leung’s art criticism shares a dual aim – to reason art, and to change the status quo. Her straight forward personality is duly reflected in her powerful art criticism pointing directly to myths towards analysis artwork, or the less than agreeable phenomena in local art scene. When art criticism interprets the world with words, the creative process of art does so with intellectual perspective. They together complete a dialectical process. It is through writing and creation that artists and art critics engage in constant dialogue, which brings diverse voices to art and fuels cultural development. Anthony thinks art criticism should start with the visual and emotional experience with the art piece, followed by communication with artists. The latter helps to explore the thinking process the artists engage themselves in, as well as the socio-cultural background involved. Her art criticism does not only offer microscopic view at individual work in multiple perspectives, but also macro ones towards the art ecosystem. Her work critically arouses public’s concern on cultural topics. She applies the abstract concepts in theories when breaking the conventional ideological framework. She does not only offer multiple meanings in the creative process, but also set forth a direction for ongoing cultural discussion. In all, she is a powerful agent for cultural evolution.

Art Criticism – what for?

The styles of art criticism vary, yet they share a common aim – to envision the formulation of art discourse and shifts in cultural trends through examination of the development of artwork, exhibitions, and art ecosystem as a whole. Their joint effort in stretching the platform of art as one public thinking machinery does not only initiate multiple perspectives for reflection, but also generate cultural discourses uniquely fit the contemporary society.

How close we have come to being rich

Text/Yeung Yang

In a recent public forum at the College Art Association Annual Conference in Chicago, scholar/curator Bruce Barber compared the curator today to the hedge funds manager, whose goal in managing assetsis to reduce risk. The metaphor was intended as polemic to begin a critical examination of the complexity of the economic position of curators working in institutional structures today. What impressed me about his presentation was that in the act of critique, it affirmed the importance of expanding the dialogical possibilities of curating and curators’ constant self-questioning – curating could contribute toas well as fail art. While curating has consequences on art, curators could make choices that mitigate the consequences.

This essay aims to invite artists in Hong Kong who are skeptical of curating to give curating a chance. The skepticism may be a product of complex circumstances, but some doubts artists may have are well-founded. For instance, how many curators in Hong Kong do studio visits, spending long periods of time with artists to learn about their works as an end in itself, not for meeting exhibition deadlines? How and how much do curators speak critically in public about their reasons for working with some artists and not others, making choices informed not only by personal taste, but by artistic contribution, or accountability and ethical positions? The less such questions are discussed openly, the more rigid the barriers of forging trust become. We end up not seeing each other as whole persons in a peer community. This would definitely fail art.

Stepping back from how curating has unfolded in the contemporary world, in order that historical reality does not limit our imagination of ideals, I propose that curating is an activity of conferring value upon objects of art - objects in all facets of the term, from bounded physical entities to spatially, temporally, socially, and technologically mediated systems that are generative, site-specific, and open. They are chosen and gathered in specific ways as objects for attention and contemplation in such settings as exhibitions, projects, events etc., where their specific values in relation to each other are attended to. Atthe same time, curating is also an activity of conferring value upon art in general. To choose to curate artis to regard art as a good to pursue; to curate well is to bring about the good of art, in its specificity and generality.

While curating is commonly seen as the individual expression of a curator, I see it also as the expression of the curator’s submission to the force of the disparate objects of art made by other individuals – the artists. To curate is to find ways to let her own and others’ ideas sound out each other. This encounter is productive by enabling a nexus in which the value of each other in a certain public realm (varying between the chosen forms of presentation) could be deliberated. I have recently encountered two exhibitions in the US, in which specific curatorial gestures encourage different ways of thinking about the exhibits and art in general. They are telling as to how curating could indeed be an activity of valuing art,and failing it.

The official narrative of The Way of the Shovel: Art as Archaeology, presented by the Museum ofContemporary Art Chicago, is that it questions history and its truthfulness. The shovel is presented literally, as artists dig and excavate and as their works address such labour. The shovel is also metaphorical in that it returns art to the matters and materials that come before it as ‘art work’. The curator and artists make it clear in the audio tour (http://shifting-grounds.net/exhibition.html) that theyare not doing scientific archaeology, and there are differences between what artists do and what archeologists do in relation to history. My problem with the exhibition is whether the way the materialsare presented live up to what it intends. For instance, accompanying the photographic work of Jason Lazarus entitled “Above Sigmund Freud’s couch” is a caption that says, “the artist ‘excavates‘ the ceiling” (above Freud’s consultation couch) in what is “probably the most revered excavation site in thehistory of psychoanalysis.” Not only does the caption compete with the title of the work by being repetitive of it, but it also risks adding an unnecessary dimension of popularism to the interpretation of an ambiguous and complex image that conjures up a mixture of noise, anxiety, solitude, power, anddesire, which has nothing to do with the sentiment of reverence to an excavation site. It is possible the curation intends to make us complicit of the gaze of many, but to what effect? what does this shared act of looking make us, and make the act of the artist looking? Guidance along this line of thinking is not tobe found. Instead, along this exhibit and some others, captions tell visitors to listen with their mobile phones to the narratives of psychoanalysts and archaeologists on the particular object on display and its context. Surely, to include experts’ opinions is to encourage understanding. But what kind ofunderstanding? If artists know in ways that are different from how archaeologists know, what does thiskind of disciplinary narratives introduced as explanation of the art do to the art? While the curation draws on established disciplines to explain itself, as if its loyalty to them needs no questioning, there is no concomitant acknowledgement of the specificity of the artists’ contribution in ways of knowing, or un-knowing. This treatment of the artists’ ideas risks neutralizing art into a set of didactic narratives that tell us how we should make of them. The original intent of acknowledging artists’ ways of working with history becomes subordinated to what is already established as legitimate and taken-for-granted ways of working with history.

On the contrary, Live Archive, coincidentally also by Jason Lazarus at the Contemporary Jewish Museumin San Francisco offers a different kind of curatorial gesture. It creates more open parameters and exertsmore challenging demands on viewers to consider the exhibits. The exhibition begins with an installation entitled ‘5/19/12 2012, Glow-in-the-dark tape’. The caption offers a story of how the tapes were‘salvaged’ from a dark room that is now closed. The caption ends by saying, “As way-finders for both the students and the medium, these sections of tape suggest new directions in practice and pedagogy delineated by the loss of the tape’s usefulness. The skillful attentiveness required in the darkroom has been largely replaced by the ubiquity of digital photography, and the effects on the future of artistic production are still the subject of speculation.” The tapes are obsolescent; but the meaning of what is rendered obsolescent in the way history unfolds itself is kept uncertain and open.

Photo:Jewish Museum San Francisco

Photo:Jewish Museum San Francisco

To find the way-finder, one must look all the way up towards the uppermost corner of the wall; two,roughly six-inch tapes are placed in the sign of multiplification. Then, making a sharp turn into a differentcorner, one is greeted by three walls full of emotionally-charged protest signs made in artist-ledworkshops in response to Occupy Wall Street in 2011. Among them are “I’M NOT A ‘HUMANRESOURCE’. I AM A ‘HUMAN BEING’.”, “SORRY FOR THE INCONVENIENCE. WE ARE TRYING TO CHANGE THE WORLD.” Together, the poignancy of the tapes at the first corner and the deafening silence of the protest signs in the next conjure up a moment that compels our reflection on the agency of our subjectivity and its limits in the world we live.

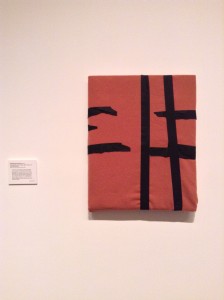

In the same exhibition, a blanket-wrapped red-brown object, with black gaffer taped horizontally and vertically across it, is affixed to the wall. It is entitled Untitled (New Orleans) 2011. The caption, written in the first-person narrative, tells of how Lazarus found the board of dated African American photos fixed to it in a junk shop. According to the shop, he says, it was salvaged post-Katrina. The artist bought the Board, so “the shop wrapped and taped it up.” The exhibit is shown the way it “left the merchant’s arms”. No photograph is shown, but there are as many as one could imagine.

There could be incessant debates on whether any single object in this exhibition, considered in isolation,is art at all. No claim has certainly been made either way. But in where and how the exhibits are placed in relation to how the gallery space unfolds and in relation to each other, their historical references are addressed but also suspended, to free up the possibilities of a different set of politics and aesthetics where they are. Lazarus treats the exhibition as “processes of learning” that take place between the artist and others. The ambiguity and tension in meaning are kept open for pondering. In this curation, the artist’s personal memory does not become an authority by first-hand testimony. Rather, it is sensual and fragile, and becomes a powerful critique of modern systems of preserving memory, an insight shared by Pierre Nora. Elsewhere, I have discussed his ideas from the essay “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire”1. For the purpose here, I would reiterate how he questions modern systems of memory preservation (museums, archives, monuments, etc.) for being sites of remains that deritualize our world. 2 While common responses to this misplaced politics is to present memories as objects of individual possession, Nora argues instead that it is the activity of remembering as lived experience that is at issue. To care for sites of memory is to care for remembering that is “at once immediately available concrete sensual experience and susceptible to the most abstract elaboration”3 (my emphasis). The question for the problem of memory is then shifted from what to remember to how to remember. As an example, Nora cites the observance of a commemorative minute of silence, a “concentrated appeal to memory by literally breaking a temporal continuity.”4 Lazarus’ Live Archive resonates. It calls for minutesof silence that are also dynamic sites for remembering. The artist’s process of thinking and questioning is an integral part of the exhibition, opened up as a series of choices made in the curation: what to controland what to let go of, who is involved and how etc. These choices all play a vital role in conferring value upon objects of human life. The way they are makes the exhibition - a temporary intervention in life -meaningful.

*引自(what about參考:Tove Jansson’s essay “The Stone”, collected in Sculptor’s Daughter, A Childhood Memoir (1968).

^ 藉此感謝亞洲文化協會獎助金, 讓我有機會經歷文中說及的所有, 並感謝中文大學大學通識基礎課程, 允準我暫時離開教務.Any error is mine. 如有錯漏歸於作者。

And you are now a star and I'm still no one ─ Brief notes on female artists in my time

Text/LEUNG Po Shan Anthony

Female artists “made disappearance”

This is a “by-product” of my Doctoral thesis. I was having an interview with my artist friend WONG Wai Yin on the topic of motherhood in a café located in an alley in Hung Hom back in December 2013. She mentioned a work on display in her solo exhibition during residence in New York – in which lines of various colours were gelled into lyrics from a song by Radiohead – “And you are now a star” on one side, and “and I'm still no one” on the other, with the “you” in the lyrics referring to her artist husband KWAN Sheung Chi (born 1980). He is her idol. She loves him dearly.

On the hand as an art critic, I felt utterly sorry for her – why is she who always got wiped out by market force as he stays?

Wong Wai Yin

ISCP Open Studio

Exhibition View/ 2009

“But I’m still no one. And you’re now a star”

Wong Wai Yin

ISCP Open Studio

Exhibition View/ 2009

“But I’m still no one. And you’re now a star”

That encounter explains my attempt in a seminar themed at Lee Kit. I led in the talk with names of female artists from the Faculty of Fine Art of The Chinese University of Hong Kong: TSANG Chui Mei (Born 1972), KWOK Ying (Born 1977), AU Hoi Lam (Born 1978), WONG Wai Yin (Born 1981), Sarah LAI (Born 1983) all the way to WONG Ka Ying (Born 1990), while deliberately skipping their male counterparts. With the indisputable fact that “Hong Kong art has been too good for too long. (quoted from Frank Vigneron) Hong Kong women artists are too good to be mentioned”, it doesn’t really matter if they like the categorization of “female artists”.

I intend no categorization according to styles, but elaboration on their common problematique. Across generations during these somewhat 20 years, painting remains the axis of ideas among these female artists. It all starts with their positive or opposite relationship with painting– notwithstanding the media involved, and the nature of that “connection”.

Painting as object

TSANG Chui Mei Fragments and Sediments Acrylic on canvas/ 122 x 153 cm/ 2013 (Photography: Eddie , Lam Chi Ying)TSANG Chui Mei (graduated 1996) and KWOK Ying(graduated 2000) both picked painting as the sole medium. Tsang has been painting continuously for the past decade or so. Through the tactical application of colours, brushworks and layers, she delivered distinct sentiments while exploring on the constant subject, immersing herself in the space of the frame. Kwok on the other hand has been toying around the concepts of painting and objects, and deliberately confusing viewers’ sense of touch and vision. Daily objects “restored” in a plane were magnified and viewed in micro-detail: Works like tiles drew straight to the wall, plane-imitating door carpet, created a sense of unfamiliarity to viewers. Nonetheless, Kwok has recently shifted focus from practice to exhibition curation.

AU Hoi Lam My Father Is Over The Ocean: 60 Questions for dad (or myself) Varying size/ 2013 Exhibition photoAU Hoi Lam, TSANG Chui Mei’s roommate at Fontanian, is possibly a representative in the aspect of “painting as object”. She went even one step further by standing in front of her own work – expressing the biographical narrative through abstract shapes, colour planes, numbers and micro patterns. She might sometimes make use of the thickness of the painting to emphasize on the side of a work, just like creaming a sponge cake; at other times she might press the painting into a thin and smooth handkerchief. What stunned you most is probably the abstract format that seemingly deprives you of direct relation to the numerous stories to be told through the work. She might even refuse to give a word on what is actually going on after fetching you figures, time and venues, and confining you on a surface of rich texture – with repeated layering, treading and binding. After completing her Master degree in Fine Art, she even finished another thesis themed on Foucault. She rendered more in-depth exploration than abstract eroticism by dragging herself between subjectivity and truth. In My Father Is Over The Ocean, a solo exhibition in memory of her father, Au dismantled items full of personal memories, put them in order with traces of marks and colours on exercise books; Dates moved forward while time traveled backward – in search of the origin when nothing’s lost. The shift from highly compressed emotion to its free expression makes it the most touching solo exhibition in 2013 for me.

Artist in front of the work

WONG Wai Yin (graduated 2004) has also been toying on “painting as object” and yet took a “reversed” path. She stepped even further than Au, by firstly performing wonders on items that bear least resemblance to art, and then humorously posing the delicate question: “But is it art?” to viewers. She imitated daily goods and tools with paperboards (which is not only LEE Kit’s favorite material); and reproduced posters at art museums with pale watercolours. She even mocked herself with her introverted personality in her New York solo exhibition “One you might understand. One you might not understand.” The exhibition includes works such as two versions of portfolio (A portfolio out of context, A portfolio people might understand) and a cable with plug at both ends (a clear mock of the so-called “networking” in artistic circle). Wong’s work can well be classified as institution critique, but the true value lies in her witty application of material in various media like painting, objects, photography or video recording.

Sarah LAI A knife and a black fruit 36 x 41 cm/ oil paint/ 2013. Ways to display fruits VII gypsum and plastic/ 2013.Tracing their common path, I asked Wong if there were any noteworthy young artists out there. She suggested Sarah Lai, saying, “Her paintings are good. And she’s a sober brain”. She was the “covergirl” for the “artistic village” feature by City Magazine back in the issue of January 2012. Graduated in 2007, Lai had Lee Kit as her tutor in her university years. Both Lai and Lee built solid foundation in painting in their secondary school years and advanced to a more conceptual development in tertiary ones. For Lai, music is her muse (she loves listening to Noise), and personal feelings became the first consideration when it comes to choice of subject. Lai differed from Lee in the sense that she still focused on famed painting in a truly “scientific” process – She would either retrieve her ideal image online, or photographed daily goods before “reproducing” the item of her choice: a cloud, a diving platform without athlete, or a piece of butter, on canvas. Though “real”, these objects were isolated after partial retrieval. The scene even looked cyber with her intentional application of low value in saturating and hue, and subtle twists in the confined tone. The installation on display in Art Taipei 2013 successfully restored the still object to a 3-D sculpture: A pale-purple peach and a yellowish-white lemon in a real fruit basket, plus an oil-painted sharp knife, all accentuated a sense of drama beyond description. This search for “truth” in media and “re-media”, and a Y-generation reflection, opens a whole new world of presentation from Tsang’s generation.

Strategic use of labeling

WONG Ka Ying Friends Fuji Instax Wide Film/ 10.8 cm x 8.6 cm/ Set of six/ 2011Shall one avoid the identity of “female artist” or embrace it strategically? It looks as if there is no need to bring the topic up again in an artistic circle which feminism raises little interest. As a fresh graduate last year, Wong raised eyebrows by playing the concept of bad girl feminism to the full – printing pictures of her naked self on the exhibition brochure, inviting “uncles” to keep her as call-girl. Her graduation showpiece, however, returned to pictorial plane with sexual and political taboos unveiled. Would this explicit feminine declaration stand out from the pool of “docile paintings”?

My practice in Ink art – A detour from fruitful foundation predecessors built?

Text/Chan Sai Lok

Hong Kong artists have enjoyed their privileged position in the rising tide of Chinese style art in the international art scene; while works by the post-80s’ and post 90s’ artists in response to unique Chinese traditions and social changes are less on the spotlight, Chinese ink art is said to be gaining popularity, albeit its unclear prospect. Hong Kong has been playing her crucial role in modern Chinese history: as the bridge between China and the rest of the world, and a cultural shelter. Literati from southern part of China not only advocated national arts in the colony, but also endeavored to renovate traditional Chinese art with novel ideas from the west. Freeing from conventional media, Artists could show their concern for Chinese culture through new ones like installations and videos. But for those who have found the beauty in ink art, how do they incorporate Chinese cultural traditions into western artistic discourse?

Up and coming young Hong Kong artists specialized in ink art are often generalized as a new generation mixing east and west with inheritance for both Chinese painting and calligraphy. That said, have we ever realized the critical condition young artists have to endure in the pursuit of ink art? Have we ever cared about what cultural habitat these artists need to prosper?

Artistic ideologies and cultural context are simply inseparable from each other. Traditional calligraphy and ink painting could not avoid the hit when feudalism collapsed in China, a time when cultural glory of the literati and painters existed barely in name. We might as well doubt after exploring multitude of ink art trends across dynasties, possibly through our smartphones: How will Howcontemporary ink painting, with deep cultural root, progress when cultural traditions should neither be abandoned nor rigidly followed? Back in 1960s and 70s, Lui Shou-kwan gave lectures at the current School of Continuing and Professional Studies of CUHK, while his students wrote “Lectures on ink paintings” as a detailed account on his revolutionary concepts on Chinese painting. ‘Yuan Tao Painting Society” and “Yi Painting Society”, influenced by Lui, were then established. At a similar time, Mr Liu Guo Sung, grand master of contemporary Taiwanese ink paintings, was appointed the head of Department of Fine Arts in CUHK. He successfully brought new elements into the “New Ink Painting Movement”. “Hong Kong Modern Ink Painting Society” was later founded.

The contrasting terms “Chinese painting” and “western painting” stress the differences in cultural traditions and material application. According to Liu, “ink art” established itself from Wang Wei in Tang Dynasty. It differs from the internal tendency of Chinese painting in the sense that it includes western artistic concepts: intense sense of contemporaneity plus free creativity. It is evidently a detour from the traditional with visual and spiritual correspondence to Chinese traditions. How does the essence of “New Ink Painting Movement” - a chapter in Hong Kong art history back half a century ago, live through till our times?

Successors take the fruits?

Respect for the past and predecessors are two key qualities in Chinese art. It is they which make it differ so much from the rebellious and unruly nature of the west. However, Wucius Wong pointed out clearly in 1950s that “Chinese ink paintings are becoming rigid and standardized, clearly disconnecting itself with times and environment”. It certainly takes much devotion to turn these characteristics a driving force of its development instead of a hindrance. Wilson Shieh, Koon Wai Bong, Pau Mo Ching, Chui Pui Chee, Lai Kwan Ting Sue, Leung Yee Ting Eve, Barbara Choi Tak Yee, Wong Xian Yi, are probably the leading players.

Lai Kwan Ting Sue “Tourists”(Partial), 175cm(H)x 85cm(W), 一Set of two, Ink on paper, 2013Respect for the past - to display traces of artistic traditions in one’s artwork, is not only a theoretical discussion, but sharpening of skills through continual training. Colour filling with a pen in traditional Chinese realist paintings is a negative example showing how lack of refinement in subject matter and skills would devastate an artwork. As it is agreed that there is no way to advance in skills except meticulous training, one can easily see why young artists hoping to master the skills have to win approval from those predecessors, though the latter are not necessarily advantaged.

The background of instructors also counts in an apprenticeship. Pupils will focus on animals drawing if their master is an expert in that area. This is particularly true in arts institutes in China. To be creative may simply mean filling the gap between ink arts and daily life, but it is also like walking a fine line – exploring an area of unknown width and depth by bringing personal elements in the creative process after paying due respect to the past, and to instructors. It’s just a matter of luck when it comes to the ending – you may hurt yourself deep or succeed in detouring from the conventional. Predecessors may criticize the creative approaches as “fun for kids” or “unskillful”, joining the media which tag them as “rebellious”. Frankly, one may be at a loss for words for responses to these comments. Prize-giving might be a common approach to compliment young, talented artists on their creativity in different areas. However, if a young artist practicing ink art is lucky enough to be awarded, he might be worried more than happy, for he has to be psychologically prepared for cold comments from his predecessors. Master and pupil may make good partners supporting each other in the creative process; there are also real examples of master and pupil turning strangers just because they “part their ways”.

Pau Mo Ching《Taking Shapes.Yoga Series》

Endless Prosperity?

Pau Mo Ching’s strikes a perfect balance between respecting the past and creating the new. She personally practices yoga regularly in recent years, and her calligraphy works see a combination of “bridge” and “tree” postures and emotional reflections, just like those expressing their mind through paintings after a joyful trip. This emotion-driven creativity is also seen in Chui Pui Chee’s calligraphy work “Three stages in life”. The semi-cursive script and grass script are historical calligraphic forms, but what strikes the nerves of Hong Kong people are Eason Chan’s hits: “Bicycle”, “When Grapes Ripe” and “Salon”. National arts need injection of youth elements for revival. While it is indisputable that gaps exist in generations practicing ink arts, the aura and underlying rules are what govern the development of talents.

School of Fine Art, CHUK has been playing its central role in Chinese art education. Basics in calligraphy, Chinese painting, scenic painting, animal painting and portrait are all individual subjects. Features on calligraphic history, painting history and Chinese art history consolidate students’ foundation. Students are still allocated time for Chinese art even after the restructure on courses. Students in the School of Visual Arts of Baptist University of Hong Kong, which has a history of less than 10 years, are only focused on visual art courses in their 3rd and 4th year of studies. If they pick relevant electives, they are bound to grasp techniques for all types of Chinese painting mentioned above in just 26 lessons! It is therefore nicknamed “near-professional interest group”. We could only spare ourselves from a lonely, boring creative process if there are support from counterparts, and “knowledgeable listeners” to share our views and feelings.

Chui Pui Chi《3 Stages in Life - “Bicycle”, ”When Grapes ripe”, “Salon”》

30cm(H)x 50cm(W),Set of three,Ink on paper fan,2013

Building the Cultural Habitat

Western art has always been the target of the capitalist international art scene or market. Chinese art, on the other hand, is a symbolic cultural identity attractive to foreigners. Ink artworks – a combination of traditional artistic content and foreigners-readable elements, could sell in exhibitions or merchandising platforms, are therefore the most popular. However, that doesn’t bring any positive impact on local cultural discussions. While the market wouldn’t value artworks from the perspective of Chinese art, can exhibitions be viewed this way? We indeed need in-depth discussions like Chiu Kwong-chiu’s search for “vivid charm” – as the supreme aesthetic and appreciation principle, but not as governing rule for creativity. We also need open-minded and daring predecessors in paving new ways. An example would be the late Seeyeu Jat creating human body calligraphy at the invitation from Cosmopolitan back in 1996. It’s high time to restart the poetic yet practical “fulfilling oriental dreams in the west” discussion approach of the New Ink Painting Movement; Exhibitions similar to “The Origin of Dao” held last year by Hong Kong Art Museum, like international academic conferences, need to be run on a continual basis.

History is not meant to be carried to the grave. The city’s once blurred identity has taken shape gradually. As Lui mentioned earlier, “The art and culture Hong Kong builds live on with the city”. With a cultural background distinct from China’s and Taiwan’s, how is Hong Kong’s cultural subjectivity realized? How will the post-millennium “local new ink art” be molded?

Get famous when young: A letter to Hong Kong young artists

Text/Jeff Leung

To supplement the inadequacy in art communications and discussions, five experienced front-line art practitioners – Ying Kwok, Jeff Leung, Sai Lok Chan, Yang Yeung and Leung Po Shan form Art Appraisal Club to discuss, exchange and write on exhibitions and features as a group every month.

Following last month’s discussion on how art environment changes the ecosystem for young artists, Jeff uses a letter to analyze the current local art ecosystem and the current climate these young artists are in.

Get famous when young: A letter to Hong Kong young artists

Dear young artists,

Eileen Chang once wrote, “Get famous when young!” It shouldn’t be difficult for you, as opportunities come right from the moment you graduate.

Fame comes with graduation

You are now in a situation totally different from that of ten years ago. From mid 1990s to around 2008, fresh art graduates either stayed in communities like local non-profit art space (e.g. Para/Site, 1a space and artists commune); or worked really hard to secure overseas’ residency / exhibition opportunities (especially for media artists). Nowadays, the graduate exhibition is in itself an opportunity. For your predecessors, graduation exhibitions were their very first show. It was an occasion for friends and family to come share the joy of graduation, with minimal ties with the local art scene. These days, you start searching for exhibition opportunities during your studies, and possibly grab a few in campus or through professors’ referrals. By the time of the graduation exhibition you would probably have exhibited elsewhere already, making you a seasoned pro.

Young artists in my generation were not conscious about the concept of “audience”. They would have done well if they had treated their tutors as one. Today, you think about reporters, parents, curators and gallery staff as your audience. You naturally leave your name cards next to your works, promoting yourselves like young entrepreneurs do for their creative business. In a way I think graduation exhibitions nowadays are similar to 17th century salon shows at the Royal Art Academy – works from members of various academies filled the walls, trying to attract commissions from the royal families or nobles. While there are no longer royals, at least one or two educational or cultural newspaper reporters will do a feature on the exhibition, with the splendid title of “The future of Artists”, along with interviews of a few art graduates. Secondary school students and their parents pay visits to the exhibitions to see and compare the education outcome of their prospective art institutions. Talent agents from art galleries start to keep an eye on these exhibitions too. Today art institutions in Hong Kong are similar to those overseas as both are frequented by commercial gallery directors. These art galleries support young artists by sponsoring cash prizes for best artworks, and further by inviting winners to setup their first solo show in their galleries. All these make a graduation exhibition so much like a Project Runway - comparison and contest among peers drives competition for interviews and exhibition opportunities.

If you are not onboard in Project Runway, nor recommended for Fresh Trend Art Graduates Joint Exhibition, there are still other channels through which you are “made artists”. Philippe Charriol Foundation Art Competition, and Hong Kong Art Biennials organized by the Government are long standing open competitions. The support from gallery directors brought about the Sovereign Art Prize and Hong Kong Art Prize. Or you may simply exhibit your works at Fotanian Open Studios and catch a visit from gallery directors. The competition for becoming a gallery artist is still keen, yet you stand a higher chance as there are more galleries now.

In mainland China both non-profit making and commercial galleries sell works to support their operation. Hence becoming a gallery artist has naturally become the first step towards an artist career. Unlike artists in earlier generations who had to work during the day, and continued at the studio for creative work till late at night. Being able to fully commit yourselves into creating art – I guess this is what Eileen Chang meant by “delightfully happy”.

Between the extremes of fames

Art critic Boris Groys mentioned in Going Public, “…Every piece of art is a commodity, we have no doubt about this. However, art is still shown to those with no intention of becoming art collectors. Actually these people have been the majority of the art-going population”. We are now at a time of art market globalization under thriving creative industries. Art is for the appreciation of the two audience groups in the proportion of 1:99. The 1% flies across the globe for biennials, exhibitions, to appreciate and collect your work, either for investment, or the future establishment of an art gallery. They consume the art production. On the other hand, the 99% may just watch and participate, but not collect, but they are from a more diverse background – general public, students, researchers, curators, critics, etc. They build the demand for biennials and art festivals, buy the artists’ monographs and painting albums, and facilitate art communications and exchanges.

You may well see the differences in artistic taste between these two groups through media reports. In between two extremes lie two parties: one giving an interpretation of the local art and culture through contemporary art exhibitions (such as Alliance francaise de Hong Kong, Hong Kong Eye Exhibition Tour and Hong Kong Pavilion in La Biennale di Venezia); the other treat art and cultural actions as “Happy confrontation” (similar to the western concept of Tactical Frivolity) put forward by organizations like Woofer Ten and Tsoi Yuen Tsuen Art Festival. Both parties strive to construct the “Locally Hong Kong” discourse and cultural symbols. That said, the art industry itself is no longer a secret. Professors might not cover it in any course, but there are still plenty of art publications – ranges from art theories to survival guides and art gossips. Books like Geijutsu Kigyoron by Takashi Murakami, Money Games in Art by Kevin Tsai and Seven Days in the Art Worlds by Sarah Thornton unveil to the general public how the art world operates.

Young artists like you are always labeled “youthful” and “independent” under media limelight. Reports go on and on about how you respond to the society as well as the art market. These concise reports portray a clear individual image for contemporary artists, but lacks the ‘groups’ prevailing in other creative categories like music and drama. What attracts me most to young groups among you is that they aren’t much “made artist”.

They don’t exhibit in galleries, and they don’t appear on newspapers in the name of resistance. They may be famous on media for just 15 minutes, but they successfully inspire critical thinking towards the market and the society. Similar to Complain Choir of Hong Kong (2009-2010), a group of local creative minds follows the American Park(ing) Day Group by covering a roadside parking lot with grass every year, just to picnic and sing. They operate without core members, their numbers fluctuate, they are all from different backgrounds, and it did not matter whether they were artistic. They managed to strike a cord on the absurdity of having both rapid living pace and a crowded living environment. And realizes their actions by re-imagining how we can utilize city space creatively.

“Street Art Movement” was initiated by two post-90s young girls, by gathering participants at public space on an irregular basis to enjoy culture in the mode of a flash mob: they draw on MTR trains, and collectively capture moments of daily life for city dwellers in a book. “We are poor, but we have good taste” is their slogan. Emphasizing the practice of popular art activities apart from the high-end artistic taste, they sit on footbridges to enjoy egg tarts while singing and dancing. To them everywhere was like a flea market – a public space for night life for the public. Their life was art – without clear forms or declarations in response to social issues; yet they ‘do’ art.

Eileen Chang also said “Be famous when young! Time runs fast even if one can wait”. Perhaps we are all swimming in the great tides of times. A joke came up chatting with friends who are artists: “When it comes to Hong Kong contemporary art, curators and reporters only know those few “young” artists around their 30s. You are called a “middle-aged” artist before turning 40.” When local young artists become famous, their counterparts on international stage gave way to young collectors. Are we still going to follow the western tide, drifting in the same direction?

I mean, after being famous for 15 minutes, when you are not young anymore, you still continue your artistic life. Have you ever imagined how to meet the tides prevailing in creative industries, to become a gallery proprietor or even start up your own art museum? How far can you actually go just for creativity’s sake?

Wong Ka Ying graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts in the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2013. The focus on her works has always been explicit and radical approach. She dares. When she graduates, she shows what is in her mind in a picture of her naked self: “Teachers don’t like me, my father doesn’t like me either. I always got fucked up by boys. I hate men the most! Is there anyone out there who would keep me as concubines?” listing her mobile phone number and email address in her resume, to respond to the dilemma she was facing at that time – truly conflicting yet innocent.

Her work “Confession: He is my SUN, He makes me shine like diamonds” spreads revolutionary ideas under the name of the national hero, blending hot social topics and personal passionsHong Kong's Art Ecosystem

Text/Ying Kwok More than 1,700 art exhibitions open in Hong Kong annually (that is, at least four openings daily on average). However, this does not bring about much related discussion. Collector Club therefore initiates Art Appraisal Club, with five experienced front-line art practitioners as members to discuss and write on exhibitions and featured topics in a group discussion every month. The Collector Club Project comprises two parts: Oil Street Exhibition (from 24 January 2014 to 22 April 2014) and a non-permanent membership programme targeting collectors and contemporary art lovers who would like to explore on Hong Kong’s art and culture. Articles and discussions from Art Appraisal Club will also be uploaded to Collector Club’s website. Written by: Kwok Ying / Chan Sai Lok / Jeff Leung / Yeung Yang / Leung Po ShanThe “Art Ecosystem” in Hong Kong has undergone drastic changes over the past decade or so. The development of West Kowloon Cultural District (“WKCD”), exhibitions in shopping malls and art conventions all bring countless new opportunities to the field: Number of world-renowned galleries open their branches in the territory; Fine arts undergraduates nowadays get contracted by galleries even before they complete their studies while only few of their predecessors could do so; Art space, once the key platform for artists, has now become scarce.

The local art scene prospers from new exhibition venues and more resources from both the government and commercial sector. However, will this bloom provide diverse manifestations or turn singular by market forces? What situation do local artists find themselves in? Art Appraisal Club explores on the above issues in its debut article.

Ying Kwok: What do you think makes an ideal “Art Ecosystem”?

Jeff Leung: My ideal Art Ecosystem is where each component, including art museums, galleries, art space, art critiques, curation and publications, evolves as times and society change. Examples include commercial galleries replacing non-profit-making art space as main exhibition venues, and increasing number of art magazines (with more art news than critique) brought by the thriving art market. I think there is a lack, not only of breakthrough in the development of local art critique and curation, but also of private foundations and exhibition organizations supporting local art, in the past ten years.

Ying Kwok: The first feeling I have after my 10-year departure from Hong Kong is that independent art space for local artists has shrunk. Where can local artists initiate experimental projects now? Of course many would pick their own studios. While this favours small group interactions and in-depth discussions, I think it is no match for independent art space. As it diminishes, so does the power of art to be viewed, to inspire and to facilitate exchanges. This also partly explains the current situation of art critique and curation Jeff mentioned. The limited room for development does not only hinder the growth of new curators, but also of those quite experienced. This is the gap I witness now.

Chan Sai Lok: The image of “artist” has always been vague for locals. When trying to comprehend the recently prominent grand concept of “Art Ecosystem”, we are at a loss like when navigating a vast rainforest. When it comes to “ecosystem”, I think it shouldn’t be just about elites or those “insiders”. Whether the public feel free and easy or not, when they participate should also count. The “WKCD effects” bring involvement from commercial organizations, but not growth in independent art space. Do public actually need art at all? This is a genuine question that has never been seriously discussed. Is the public just beneficiary of art? Do they recognize the value of art (but not art pieces) on both personal and social level? Who are viewing, appreciating and discussing art at a time when art activities are among many choices of consumption and entertainment? When art exchanges remain superficial, and neither discussion-inspiring professional art critiques nor mediators are present, I think there is a dire need not just for in-depth discussion on art, but also for internalization of artistic concepts.

Yang Yeung: My answer to this question is two-fold: Internal and external conditions, and principles at other important levels. Let me focus more on internal ones as Jeff and Ying had discussed the external ones. First, Equality: are we treating or preparing to treat every art form as equal so as to extend this approach to the society? Second, Mutuality: we need to acknowledge our mutual influence and protect our equal rights of expression. Are we showing enough mutual support, trust and understanding? Third, Freedom: what makes us free as practitioners of art in this society? Is everyone equally free? What is artistic freedom in connection with Equality? Fourth, Room and time for deliberation – in relation to all three above, do we regularly practice (and value the practice of) deliberating the above principles of our survival? Last but not least, there are many more under-explored ways to talk about art than existing, established ones.

Leung Po: I would rather talk about art than “Art Ecosystem”, for the latter would bring a fruitless discussion. Recently I am reading High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture (2009) by Isabelle Graw, in which the author further develops Bourdieu’s theories. Bourdieu discusses the “myth” between art and money - the self-discipline principle of the field of culture and art engages in relative autonomy with external fields like market. Simply put, art objects to whatever market supports. Graw, however, thinks Bourdieu is only telling part of the fact – The mutually dependent relative heteronomy has also long existed between art and money. This is particularly true for the post millennium contemporary art market after the burst of financial bubbles. When there is only a thin line between priceless art and worthless art, we are bound to return to the materialism of art (a good example will be For the Love of God by Damian Hirst in 2007 featuring a skull in diamonds). The mass is searching for the guiding principles determining the “depreciation proof” nature of art pieces. Art critique should have played this decisive role at a time when neither the contemporary art market nor its symbolic value is clear. In the expanding art market, boards and charts quickly process (or even make up) information favourable to art investment. This phenomenon has been prominent ever since the HK Art Fair in 2008 – Magazines like Timeout would evaluate art personalities every year. These, like guidebooks to tourists, would give readers the impression that they thoroughly understand the local art ecosystem.

Ying Kwok: If we return from the overall environment to creative process itself, is the local art atmosphere in Hong Kong particularly favorable or harsh to the development of any art medium? Would Sai Lok say something about the survival of Chinese ink paintings? Would Yang Yeung elaborate on the required conditions and room for development for sound art pieces?

Yang Yeung: The first and primary thing is to provide the conditions for people to listen. Artists who work with sound as their material don’t worry too much about the availability of physical space. They are more concerned with how the conditions could be made for the hearer to listen – in various aspects in detail. When sound makes space by re-constituting them in their physicality, listening is about listening to space (as relative distances, past and present etc.). Bleeding sound in an exhibition hall, for instance, that ‘confuses’ one work and the other is in itself an interesting and productive experience of the art.

Soundpockets have never been interested in ‘existing spaces’ (perhaps by that we mean, white cube galleries, museums (or spaces that have already become routine and managed in particular ways), not because they are not interesting (acoustically and otherwise), but just that there could be so many possibilities when there is no need to prioritize the conventional. For sound to freely and fully express itself, there are many other things to worry about than just space. In general, I think it’s important to assert our right to use space – which has to do with art in general, not just the art of sound. The right to use space – public space – is regulated by slanted principles. This is a much more important front to move and challenge than the kind of space for a particular art form, for with the right to use public space safeguarded, all art forms benefit.

Sai Lok: I don’t think any art medium would flourish in the territory. Hong Kong is simply too money-oriented and pragmatic; abstract and conceptual art pieces, or works with local themes but not with any so called “Chinese” elements, could only win applause from insiders no matter how brilliant they are. Chinese ink paintings as a medium might well develop like its western counterparts. However, unique changes in environment and concepts across dynasties develop a distinctive pathway for Chinese art, making it rich and lively. The “New Ink Movement” symbolizes the connection between Chinese art and the contemporary syntax; Art museums have featured Chinese art as a spiritual ideal in multi-media exhibitions. While the Chinese artistic circle undeniably has stayed away from the spotlight, we should critically assess how well equipped curators, art critics and public alike in appreciation of Chinese art.

Ying Kwok: The group of successful full-time artists in their thirties set realistic examples for the later generations. Would Leung Po give us a brief analysis as to why male artists dominate the group?

Leung Po: I never set limits on sex and age groups. The fact that my works are gender conscious gives a misconception that my commentaries do the same. During around 2003 to 2004, I tried to sexually segregate male artists as I was particularly concerned about them. Female artists from earlier generations like Irene Chou, May Fung and Ellen Pau paved way for their successors so that female artists in my generation need not worry much about discrimination in our career. That said, I somehow see the need for Hong Kong to “enter” the international art scene. As the stubborn power and aesthetic structures have revived (Clearly seen from biennials and prizes commercially titled, to public cultural institutions operated on equalitarian principles, like museums and sponsored art space, surrendering its prime position), I see the need to set gender as the focal point again without transforming it into a consumable in the market.

Ying Kwok: Jeff, What is your view on the impact local art environment cast on young artists?

Jeff Leung: Generally speaking, the benefits art brings to the economy and society elevate the social role and position of artists. With more and more news and features on art, the image of artist (like full-time painters and conservation artists) is more vividly portrayed than ever. This in turn attracts more teens to be practitioners of art, for they do not see it just as a romantic identity, but an achievable professional goal. I see two extremes in the paths young artists take after their graduation: some got contracted into solo exhibitions by galleries; the other contribute their creativity to social movements or community developments. Young artists holding exhibitions in galleries produce beautiful works with their excellent skills. They successfully present the literal aspects of mass topics like local cultures and daily life. But there are few experimental works related to universal values, such as equality, environmental protection and war. On the other hand, artists participating in community development free themselves from the conventional boundaries set by art organizations. They are no longer merely observers and enquirers. Instead, they live their life in the community and have first hand experience in its development, Part-time artists working as farmers are a good example.

中文

中文