Annie Wan’s Food Diary of Her Trip to Tsunan - Discovering Ethics in Farming, Fishing, and Preparing and Sharing Meals

Feasts in Contemporary Art

While eating sustains life, it is also a sensual experience. Eating meals together builds relationships and reveals cultural trends of society. For those with a sweet tooth, how could they resist the sugary temptations of multi-media artist Song Dong’s wondrous city models comprised entirely of biscuits, chocolate and cream? The ‘city’ was consumed in less than half an hour, when all we had left was a sweet creamy taste in the mouth and a reflection on the false assumptions about urban development and over-consumption. Holding Filippo Marinetti’s The Futurist Cookbook in his hands, a gourmet who enjoys exploring new combinations of different ingredients will probably be fascinated by a taste experiment with rose petals, velvet and dishes cooked in champagne and devote himself to bringing out his creative ability, flowing from the tongue to the stomach. In the meantime, people can try to understand the trickery and paranoia in world politics with the flavoursome lamb, the thick okra stew and the strong aroma of garlic and onion as they learn to cook Iraqi cuisine in the ‘Enemy Kitchen’ created by the American-Iraqi artist Michael Rakowitz.

There have been numerous examples of contemporary artists using food as a medium to contemplate social and cultural issues. However, Hong Kong artist Annie Wan has no intention of using what people eat and how they eat it as a means to evaluate the world. Instead, she listens to personal anecdotes on food and finds ordinary yet omnipresent stories about daily life in the nostalgic memories of food. In 2019, the artist was invited to participate in the residency programme of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale. She initiated the project ‘Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread’, which was a record of local food exchange, in which she and Tsunan community members invited each other to their homes as they prepared and shared family dishes together. There were neither grand discussions of cultural issues nor intensive studies of new ingredients and dishes. Wan simply embraced the seemingly plain eating habits of the local people while looking for the myriad flavours of the cooking they grew up with.

An ‘Artistic’ Vision in Home Cooking

The intriguing thing is, Annie Wan is known for her ceramic artworks and for her approach to using moulding to congeal the form of everyday objects, such as books, tin cans and radios, in ceramic. Her work might involve food sometimes, but in her artistic practice she often creates replica in a playful and loving way that reveals multiple meanings of objects. How does the artist comprehend the relation between cooking, food and communities? How does she include food in her creative practice?

The ceramic artist has been expanding the concepts of moulding and casting. The light that goes through an attic window, the gap between the hands held together for prayer and the air between the panes of a soundproof window, are all moulded in clay. Not only does she give a clean shape to the void, she allows even the bulges and creases of the ceramics to carry meaning. Indeed, her works of moulding are ‘monuments of time’, translating the intangible thoughts and feelings of life into visual traces of time that have shapes and texture. It is true that the works cannot replicate the original objects, and that the specious similarity of their outlines acknowledge the loss and transience of life. Nonetheless, they capture the vague shapes of the past, which are now preserved for eternity, where meanings can grow infinitely. Her creation, which could be called ‘the art of replica’, reproduces the appearance of mementoes to preserve the vanished and irretrievable experiences and to trace the trajectory of how time passes. When the artist travelled to Tsunan, she wanted to learn the stories of local community —who are these people? How did they establish roots in this place? What future are they imagining for themselves? Although she did not speak Japanese and was not familiar with the town, she believed that food can serve as a connection between people and reflect our pursuit of goodness. During her residency, she was keen to develop her artistic concepts further by replicating Tsunan’s stories of that particular time.

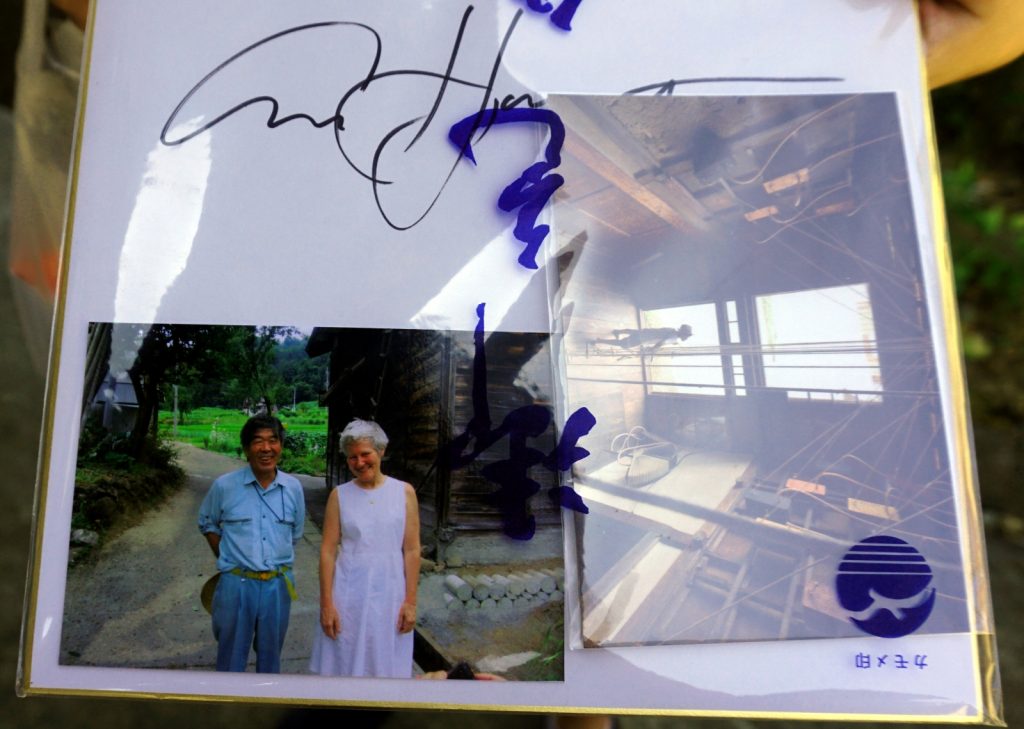

Pic 1: The artist captured the joy and sadness in life, how members of the community left and gathered, and the entirety and creativity of an individual in writing and photographs

As soon as Annie Wan arrived in Tsunan, she put on a small banquet with home-style Hong Kong dishes for more than 20 people in the town and shared with them the recipes of Hong Kong cooking. To return the favour, her neighbours invited her to workshops of traditional Tsunan food and to different households to cook their home dishes. They also dug up carrots, known by the locals as yukishita ninjin, together from the snow. While enjoying the silky soba noodles, the cloyingly sweet kintsuba and the aromatic chimaki dumplings, they shared views on hand kneading techniques for dough, the fun-filled interaction of having hot pot with one’s family and even the influence of a fish on the entire community’s taste for food. In this agricultural town, stories of food are always associated with the start of a sweet common life. Having collected food stories from her neighbours, the artist captured the joy and sadness in life, how members of the community left and gathered, and the entirety and creativity of an individual in writing and photographs (Pic 1). Food seems to be trivial and yet so fun to talk about. A meal can stir up sensual desires and memories of home for one, while another can taste the flavours of a culture and society.

Annie Wan treasured the brief time she spent with Tsunan people, to whom she was grateful for their local produce and home-made snacks. As an artist, she has always pondered over how art can bestow meaning upon a meal or a gathering. Nonetheless, how is art related to the daily lives of Tsunan people? Unlike her usual practice, Wan shifted her attention from the microcosm of objects to a creative approach that she developed from the daily farm-to-table experiences. When she was sorting out the food stories in Tsunan, she discovered tangled connections between various things, one after another—people’s linkages to themselves, to the community and to their land. This is not to say that Wan went to Tsunan to create art about food, but rather to say that her neighbours’ bits and pieces of stories provided the substance for her works. Figuratively speaking, her creative outcome is a big pot of stew, which achieves the hearty Tsunan flavour from the ingredients that the local people always had in mind and the seasoning of their life experiences.

An Imagination of a Good Life

In the exhibition space of the Hong Kong House, Annie Wan welcomed visitors with a table of ceramic food—corns in creamy white, rice wine in soft yellow, sasa dango in nutty brown, tin cans in lovely lilac and pumpkins in brownish red—as if they were waiting for home chefs to turn them into a plentiful feast where everyone could share laughter (Pic 2) . The rich variety of ‘food’ sparked the imagination of the quiet life there, and the black-and-white photos on the walls told the visitors about the quality time the artist spent with the Tsunan residents. In one photo a noodle chef rolls out a thin dough sheet, and in another an old lady is holding a pair of chopsticks and devoting her full attention to the pot of food on the stove. With a deft twist of her fingers, a housewife finishes making a sweet soft wagashi in the shape of a flower. In no time, the chef has sliced the dough sheet into evenly thin noodles in a smooth motion… Wan chose to focus her lens on skilful hands and gestures that showed respect for food, which makes her photos become more than a record of daily life; they represent the people’s persistence in living a good lifestyle and staying true to their craft.

Pic 2: In the exhibition space of the Hong Kong House, Annie Wan welcomed visitors with a table of ceramic food.

Seeing the side-by-side contrast of the monochrome photos and the colourful ceramics, one realises that her artwork is actually a reproduction of the ingredients she and the local people cooked with and of the dishes they made together. They are the memories of food that the artist replicated, and behind them lies a yearning for the past and a loud declaration of ‘that has been’. The time that they spent together preparing and sharing food is genuine. Although everything has long gone and all the plates have been cleared, the recipes for traditional dishes have been passing down from generation to generation. Like their ancestors, the people in Tsunan are assiduous in nourishing their lives with seasonal food and skilful cooking so that their imagination of a good life will never run out.

Food Ethics—Ways of Living a Good Life

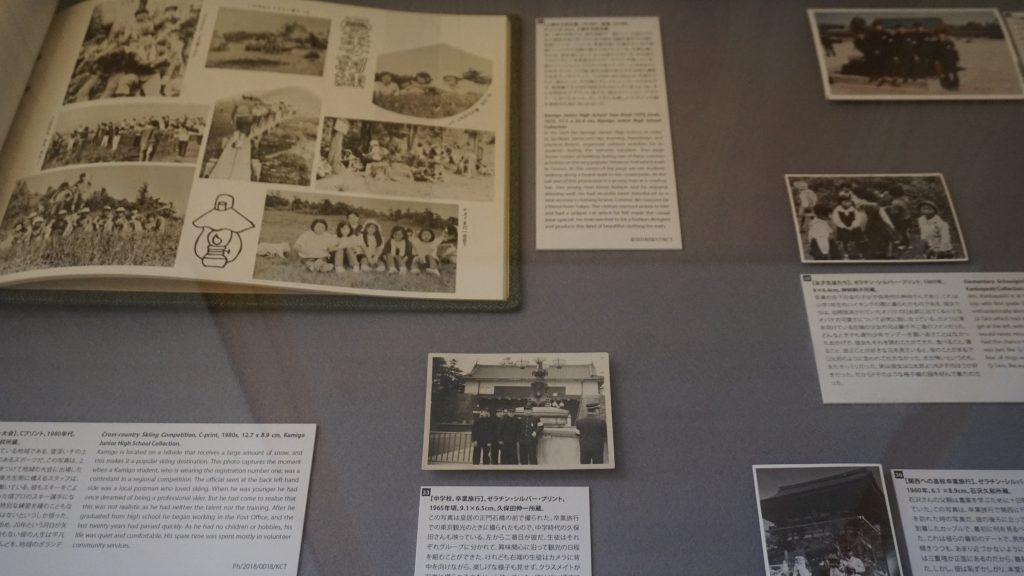

What is a good life? The artist never intended to give the illusion of Tsunan’s rural image of innocence or to endorse the corny sentiment about fellowship. She only came to realise that the local people’s love for their hometown originated from the well thought-out views about the ethics of eating during the cheery chit-chat with her neighbours at the dining table—they would think about the life they enjoy and ways of coexistence with themselves, others and the community. By retrieving the food memories of six Tsunan residents, Annie Wan, together with the visitors, thinks back on the role of food in daily life and queries how what we eat casts light on ways of living a good life (Pic 3).

Pic 3: Retrieving the food memories of six Tsunan residents

What does a bowl of rice mean to us? When Kondo Mirai went down with ulcerative colitis and stayed in the hospital for days, she constantly thought about when she could digest a bowl of steaming hot chewy rice and stop sipping the soupy rice porridge. During her hospital stay, she closely observed her reactions to different food items, learning more about her body and its limitations. As ordinary as it might seem, a bowl of rice is good enough to remind us to rebuild our relationship with our body.

In love with the delicate sweetness of dried sweet potato and happy to eat the tuber for the rest of his life, Yachida Yutaka has affirmed his lifelong commitment to growing sweet potatoes. Yamada Sakae cares for the chickens he rears so much that he only sells their eggs but not the meat. There is nothing wrong with their romantic ideas, but life on a farm is not something you should decide out of a false sense of confidence. When heavy snowfall is expected in Tsunan, Mr Yachida has to protect his sweet potatoes through the winter by pitching tents and setting up heaters. As for Mr Yamada, who does not want to slaughter his own chickens, he came up with the idea of using chicken droppings as fertiliser and mixing husks from his harvests into the chicken feed, maintaining the cycle of the co-dependent plants and poultry. From the seasonal change of spring to winter, farmers learn to observe the natural order of things and the unbreakable cycle of life and death as they grow crops and rear animals, counting the time that flies as quickly as our lives pass us by. The message the sweet potatoes and eggs are sending is not just about their nutrients but about the rhythm of life that suggests there is a time for everything. How do city dwellers know about eating with the seasons or even think of the occurrences of partings and reunions when they see the slightly charred roasted sweet potatoes and the smooth and tender steamed eggs?

We live in the present, yet are constituted by our traditions handed down through history. Tanaka Fumiko is passionate about studying traditional local cuisine. With the characteristic chewy texture that comes from mixing rice flour and glutinous rice flour, her ambo buns are filled with crunchy pickles to inject the Tsunan flavour of crisp saltiness into the dough’s fluffiness. Not only do the buns carry the warm memories of cooking and eating together with family, they also stem from the strong tradition of pickled foods in the snow country. Bakery owner Hayakawa Fumie loves using local ingredients like rice flour and carrots, and therefore has never ceased to find new combinations and methods in baking to make Western cakes full of memories of Tsunan. A bite of her fluffy spongy rice cake may remind one of the taste of their mother’s traditional rice flour sweets or of the delight in having earthy home-cooked dishes. Perhaps opting for traditional methods is like treading on eggshells—they have to think over again and again what they have preserved, why they insist on the original ingredients and recipes and methods they have followed while adapting the old ways of doing things. In the stream of time that bears us forward, we cannot cut off from the cultural environment in which we grow up, nor stay away from the era we live in. Keeping traditions alive is as meaningful as cherishing what we have, and in this way we will not lose ourselves on the turbulent tides of change.

How can we deal with life and its daily challenges in a constantly changing world? Nishizawa Kimi recalled how the lives of the three generations of her family changed around fish. In the 1920s when fish was seldom eaten in Tsunan, her grandfather, who sold wholesale fish, organised a ‘mothers’ club’ to teach housewives all kinds of fish dishes to widen the local fishing market. Mrs Nishizawa and her son and daughter-in-law opened the restaurant ‘Uokane’ in the 1980s, turning the life skill of cooking fish into a family-run business. However, Japan has been facing the challenges of falling birth rates and an ageing population despite rapid economic growth. The population in Tsunan is decreasing even further. As a consequence, the family changed the way they ran the business and started to offer bento lunches to companies and schools. Mrs Nishizawa collected her memories of food on the fishing boat, chopping board and serving tray as she ran around with fishmongers, housewives and customers of the restaurant. It may be hard to take full control of our lives, but at least we can decide where to go from choosing our food. Where does our food come from? How many agents does it pass through? What price are we willing to pay for delicious and fresh produce?

An Artistic Feast in the Community to Reproduce the Spirit of Goodness

In the exhibition space, Annie Wan used unadorned words as simple as plain tea to connect Tsunan people’s memories of food. Her colourful photos showed that everyone she met in Tsunan was in fine feather. Kondo Mirai appears to have had a steaming hot bowl of rice; Yamada Sakae, who loves his chickens and many other things, wears a joyful smile with his hands in his pockets; the enthusiastic bakery owner Hayakawa Fumie is introducing her home-made baked goods to the visitors… The artist made a piece of elegantly white ceramic food for each record of the food experience in memory of the local people who use simple food to build a good life for themselves and for the town (Pic 4). The ceramic works look unremarkable but are incredibly realistic. From the appearances of the food items, it would not be difficult for them to remember the time they spent with the artist, talking about the food they liked and their aspirations. The visitors could see the bond between the people and the town in the writing, photos and ceramic food; meanwhile, the stories of food also caused them to rethink the ethics of living with regard to fishing, farming, preparing food and consuming it.

Pic 4: The artist made a piece of elegantly white ceramic food for each record of the food experience in memory of the local people

Stepping into the lives of Tsunan people, Annie Wan used the art forms of writing, photography and ceramics to reproduce the locals’ memories of food. Her approach does not simply replicate, but oscillating between imaginations and reality, shows us how people aspire to live quietly and attempt to make things better for themselves and even for the community. As the seasons pass and the cycle of change plays out in nature, life has always had a bit of cruelty and strangeness hardwired into it. Nevertheless, something as simple as a fish can tell the story of a three-generation family working hard at their own business, and a piece of rice flour cake can tell the creative interplay between tradition and innovation. Even a small egg is appreciated for encompassing the farmer’s understanding of coexistence with all living things. Annie Wan’s art in the form of copying is not intended to make the locals’ memories null. On the contrary, it seeks to render the rich texture of life in Tsunan.

What the visitors can see are authentic food stories that took place in Tsunan, the local people’s reflections on the ethics of living, and the partnership between the artist and the residents. This is a relationship between people who have valued each other since the day they first met—the disarmingly genuine residents welcomed the artist’s visit and shared their stories while the artist, with gentle interest and sensitivity, engaged herself in learning about the local food culture, shooting documentary photos and discovering different tastes of the community life. Not only does her artwork recreate the stories of Tsunan people, but it also keeps a record of people who formed bonds despite the language barrier and inspired each other with their insights about living a good life. Holding the affective bonds between the people and place in high regard, the exhibition is more a colourful feast for the community than a stage for the artist to show off her talent. Every word, every object in the exhibition points to the upbeat attitude of Tsunan people and reveals the human sentiments shared by different food cultures.

An Homage to the Ordinary Days

Eating is an indispensable part of our daily routine to sustain life. Yet if food is prepared by skilled cooks, it will become a mesmeric experience of sensuous enjoyment. Annie Wan decided the exhibition’s name ‘Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread’ would aptly embody the food memories of Tsunan people. Taken from the Lord’s Prayer, the title is meant to express her gratitude to the Creator in a pious way, for a meal, a heartfelt conversation or simply a calm day without rain and wind (Pic 5). A good life should never be taken for granted as it is always the fruit of someone’s lifetime of hard work, perseverance and struggle. The dedicated efforts of several generations could be gone in an instant if any calamities prevails. We do not have full control over our lives. There are no expressions of inordinate desires in the prayer, but merely the petition for the daily bread because it teaches us to live a humble and frugal lifestyle. Foods might seem to be something not worth mentioning, but they require concerted efforts from different people to find their way onto our dining tables, from fishing and farming to distributing, cooking and consuming. From a macro perspective, the food supply chain is closely linked with logistics, global trade and the ecological environment. With just a photo, a mould-cast food or a paragraph, the artist tried to discover the people and stories that are connected by food as an homage to the wonderful lives the local residents have endeavoured to achieve.

Pic 5: Taken from the Lord’s Prayer, the exhibition title is meant to express her gratitude to the Creator in a pious way

To reflect on the food and life, Annie Wan put a bowl radiating warmth and subdued light in a corner of the exhibition space. The bowl was her own creation in memory of the happy times she had in the town because of food. Food vessels are nothing special in daily usage but the textured surface of the handmade bowl illustrates the infinite possibilities of earning our living with our own hands. Even more so when the artist mixed the husks of the locally grown koshihikari rice with the ash from burning Hong Kong acacia wood to produce the cloudy white glaze for the bowl. The bowl has been accompanying the human race since ancient times, and yet its shape always fits into the palms, curved and facing up as though holding food. Symbolising a container for abundant food and the joy of eating together, the bowl represents the view of giving thanks for the blessings in our lives. The residency programme can conclude with the artist’s bowl as she wishes the bowl to be filled with local produce and to spend every day with the residents.

Tsunan people, following the natural order of things, develop their own routines day in and day out, and their everyday experiences constitute the meanings of life. Regardless of how homely, random and trivial their everyday lives are, the people have travelled through the currents of time and sent out waves of wonders on important occasions, all of which has given substance and colour to their ordinary days. The artist’s residency and exhibition have opened up a shared space for the locals, where they are encouraged to use their own experiences to connect with others and show the meaning of making connections. Turning back from life in Tsunan to our usual lives, how do we define ourselves and decide what life to live through our daily choices, such as what we eat and how we eat? How do we create daily lives that we deem good?

An art festival you would always want to go back to

另有中文版

The Venice Biennale, which draws a huge art loving crowd, is like a miniature map of global power and economic relations. Documenta in Kassel is tremendously heavy with its historical archives and social justice issues around the world. When we are going to experience Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale set in a remote countryside, however, we should not hold the same attitude, the same expectation, or plan to spend the same amount of time. We can start to immerse ourselves in the local sunshine and humidity by strolling and wandering, and let our thoughts sprout freely among the hills and forests. If you cannot drive, do not mind having to spend a whole day just to see one piece of work, or having to arrive one or two hours before the work opens to viewers. If you are driving, do not go dashing along the hillside or finish off the area and the whole festival in 3 days.

Delightfully conceived and adorably designed, “The Kamigo Band-Songs for the Seasons” (M063) was set in a room in the Kamigo Clove Theatre. The band was composed of a few marionettes who played and sang about the four seasons in Tsunan. The band played a collection of 10 songs, which the viewer could choose their English or Japanese versions. It was even possible to swap languages while the song was playing. You could also be the singer behind the animal band by picking up the microphone and singing from the lyrics folder prepared for you. If you have chosen an upbeat song, you could see the octopus beating six drums and two cymbals at the same time. When you played a song about the snowy winter, a translucent fabric curtain would drop slowly. Wouldn’t it be nice to start a beautiful day by coming here for a song every day?

“The Kamigo Band-Songs for the Seasons” (M063)

One can’t talk about singing without mentioning the work “Karaoke & Humankind” (T362) from the exhibition Hōjōki Shiki 2018: The Universe of Ten Foot Square Huts by Architects and Artists. A hōjō is an interior space of 2.73m by 2.73m, which is also called 4 and a half tatami mats. The title originates from Hōjōki, a diary written by a 12th century nobleman who confined himself in a space of a hōjō and observed disasters and famine around him. Cubes of 2.73m on all sides were built around the square pool of the Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art KINARE in Tokamachi. The cubes were transformed into a living space, a theatre, a sculpture, or even a sauna. One of them was transformed into a “snack”, a kind of bar ubiquitous in the streets of Tokamachi. “Karaoke & Humankind” was open every day from 4 to 7 pm, manned by a real bar owner (Mama-san) from the neighbourhood, who would serve beer or other drinks, and would even sing with you. You can find everything you need despite its humble size. You were immersed with the atmosphere of nightclub once you get through the door, though you were just separated from the daylight and the art museum space by a thin wall. The space was so small that you could almost touch the walls if you stretch, but the room was nicely soundproof, so it was really OK to cheer and sing inside. You could choose from an array of songs in various languages including Japanese, English, Cantonese, Mandarin and Korean. It’s perhaps a bit pricey at 500 yen for a song and a drink, but sometimes Mama-san would let you sing a few more. There were moments you felt as if you have become a local when you had the luck to be joined by other museum visitors. The fun went as deep as the idea behind the project: Mama-sans, many of them have reached their middle age, often felt socially marginalized because of the nature of their jobs; the offer to take up duty at the museum gave them a sense of respect. It is a refreshing encounter with art by having a drink and a song, and a nice chat with 8 Mama-sans from Tokamachi who rotated on duty at this special edition of a “snack” bar. It is also recommended to have a bath at Akashi Hot Spring adjacent to the museum after you have enjoyed art and karaoke. The common area of the hot spring resembled a community centre more than a bathhouse. A few artworks, which would be lit up after dark, were installed in the outdoor areas of the hot spring. It was a very unique experience when you watched the art work while soaking in a hot bath.

“Karaoke & Humankind” (T362)

The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale is also about food. Kojimaya in Tokamachi is famous for its soba noodles, while sake made out of koshihikari rice has also gained great acclaim. “Hokuetsu Seppu” performed at the Kamigo Clove Theatre Restaurant was both a theatrical piece and a meal created from local history and produce. With a selection of the most seasonal ingredients and prepared with dedication, the menu of down-to-earth Tsunan delicacies included carrots harvested under the snow, edamame and milk soup, marinated pork, and “world’s most delicious rice balls”. Local culinary history, farming culture and local customs were introduced between each course. The building that houses the Kamigo was originally a school. One of the ladies who served the meal was a former student. Although not speaking a word of Japanese, I could communicate with the local ladies by means of body language.

If you are still in doubt whether the Triennale is just another art project that landed on the site regardless of context, or that visiting it might just be another form of consumerism, then why not try and stay in Tsunan for 7 or maybe 10 days? You would meet friendly and enthusiastic locals manning the entrances of the art works, and many villagers had witnessed the construction and installation of works. When I was visiting “Air for Everyone” (M037), I met a local old man, who already knew by heart which handle would produce a sound in what key. He even went home and back to show us his photo taken with Ann Hamilton. There is also one advantage of not driving: you could chat with fellow passengers on the art festival tour buses. I have met a professional art consultant from Berlin, an employee from an art gallery in Taiwan, artists, art students, a trainee from the tourism board of Tokamachi, or even art students from Hong Kong. Even when you ride on a train that runs only a few times a day in the Iiyama line, you would see familiar faces. I felt that we were together at least for a short while, though we had exchanged nothing but a passing nod or goodbyes. You would actually find the mood that the art festival wanted to offer you, by starting a random conversation with whoever you might meet as you relax or wait for the next train in the Ikote (T309) restaurant or the café in Nunogawa campus (D331). What is important is that, the Triennale is not just something that happens once in three years, but is somewhere that you will always return to.

Photo with Ann Hamilton

Photo with Ann Hamilton

You might miss some unforgettable experience if you rush to one art work after another in the fields following the crowd. Kingsley Ng’s “Twenty-five Minutes Older” (A004) was transplanted from tramways in Hong Kong to a tour bus in the Triennale, and the landscape that you saw has changed from cityscape to rolling mountains and rivers. But that was precisely what was disadvantageous to the work, as landscape seen through thick foliage was not as explosive and varying as the streets of Hong Kong. Here it is probably more enjoyable just to look outside the bus window than from the projection created by the artist; that means ingenuity of the artist was probably wasted here. Creation and production of art have to adapt to the different contexts in which they are shown. Viewers also have to let go of their preconception.

“Twenty-five Minutes Older” (A004)

“Twenty-five Minutes Older” (A004)

Fiction in photographs and reality in fiction – Tsunan Museum of the Lost by Leung Chi-wo and Sara Wong

可轉中文版

Old snapshots spark off memories. Stories and emotions are recalled, be them your own or strangers’. Photographs, as they capture a particular fraction of a second, serve as material remains of past events and are closely linked with reality. Who are these people in the photographs? How are they related? Where is this place, and what happened there? Each detail is connected to endless anecdotes. It seems that history, time and stories are crystalized in these images.

Photographs have replaced facts as tokens of history. The camera is ever present during gatherings, trips, festivals or community events. During their call for old photos, Leung Chi-wo and Sara Wong visited five families in the district of Tsunan (Are they the families of Mr Kubota, Mr Moriguchi, Mrs Nisizawa, Mr Nakajima, and Mr Ishizawa in the stories?). The artists have also made a selection of photos from school albums, historical photo books and newspapers, and then written stories about them. From the forty-odd photos selected, it seems that the artists were trying to discover personal and “small” history from once prosperous fields, customs and people, as apart from the grand narrative of History with a capital H. Home visiting is a means to establishing relationships, and to share family albums is not just mannerism for receiving guests, but is a bond of friendly trust. To re-create history with a small “h” is to break free from the narratives of History with a capital H.

Leung Chi-wo and Sara Wong demonstrated interesting perspectives on the photographs by focusing on random people who were accidentally captured with their backs to the camera. After having registered every detail of their poses and costumes including tailoring, fabrics, colours and accessories, these random strangers were re-enacted by the artists and once again photographed in a studio setting. The very act of re-creating these characters in photography demonstrates how much in details and meticulously the artists have looked into the original photographs. The sharp and brand-new images, isolated from the context of their time, blur the distance between past and present. The absence of any background makes it difficult for the viewer to determine the identities of the characters, the location in which they were placed, and the context of what was happening.

On top of being vessels of images, photographs are also interpretation of real life. However, the photograph only preserves the appearance of a split second, without recording any meaning. Meaning was born as a result of the viewer’s interpretation of the image. The most “loyal” and popular method of generating meaning is to interpret or postulate according to the context of the photograph. Therefore, the meaning of photographs has always been varied and full of ambiguity. When I was trying to understand the stories behind the photos from the accompanying text, I encountered information that should be inaccessible to the artists, as I dug into a few paragraphs. I often found similar issues such as social movement and gender roles recurring throughout the narrative text.

Text is not just a tool to organize information, but is a creative medium as important as the photographs. Detaching these old Tsunan photographs from their context, Leung Chi-wo and Sara Wong enlarged the possibilities of fictional narratives. Their fictional contribution steals its way into the memories of those families. The discovery of the fictional in these texts is also a discovery of the possibilities of how meanings of photographs can be created.

Almost life-size, these photographs painstakingly mimic people from real life. Details and backgrounds about these people, however, were created with a sense of drama as in fiction writing. The design and use of Hong Kong House, built on the site of a dismantled village house, have no apparent connection with the village in which it is located. Tsunan Museum of the Lost is suitable to be displayed in the setting of a white cube. The fact that this exhibition and the style of Hong Kong House match each other seems to be a metaphor on the fact that, some artificial additions are inevitable in every art festival that aims to merge in with local environments. Art is not above everything, and it should never be regarded as a mere tool. After all, what artists could do on earth is, making art.

Life is full of imperfections and loss. No matter how important it is to revisit history, we cannot deny the fact that digging into the past is a process during which we face our loss. What we have “lost” is not only our knowledge and feelings of Tsunan, but also the motive to comprehend the past through old photographs.

31 July 2018

Ann Hamilton's Air for Everyone (2012- ) @ Echigo-Tsumari Art Field (Echigo-Tanaka): The artist makes the house breathe. Of the many conditions of life the artist gives expression, I am impressed the most by the way air is simultaneously a bagful (at rest), drawn through bellows (as music), conveyed and connected by open windows (as wind), trailed from wall to wall (as imaginary & broken music), sculpted into a single long chime (as instrument)....all of which coming into awaking a dwelling. One sees here and hears there; one is here and is there. Modes of embodiment keep gently shifting. In the middle of the house, one pulls a string hanging from the ceiling to make a bellow swell; at the gesture of release, the bellow seems to let out an elongated sigh. I imagine how this might come close to being inside the belly of an ancient tree: whereas from the outside, it inspires awe, from the inside, it imparts safety, warmth, and an understated marvel. (Yang Yeung)

Ann Hamilton's Air for Everyone (2012- ) @ Echigo-Tsumari Art Field (Echigo-Tanaka): The artist makes the house breathe. Of the many conditions of life the artist gives expression, I am impressed the most by the way air is simultaneously a bagful (at rest), drawn through bellows (as music), conveyed and connected by open windows (as wind), trailed from wall to wall (as imaginary & broken music), sculpted into a single long chime (as instrument)....all of which coming into awaking a dwelling. One sees here and hears there; one is here and is there. Modes of embodiment keep gently shifting. In the middle of the house, one pulls a string hanging from the ceiling to make a bellow swell; at the gesture of release, the bellow seems to let out an elongated sigh. I imagine how this might come close to being inside the belly of an ancient tree: whereas from the outside, it inspires awe, from the inside, it imparts safety, warmth, and an understated marvel. (Yang Yeung)

30 July 2018

Reports from Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, around #HKHouse: end of my morning hike blessed by 'gifts from land': tomatoes from grandma at 魚兼本店居酒屋(https://r.gnavi.co.jp/404pn8v10000/), as if a prelude to #Gift_from_Land by Sense Art Studio + HK Farmers + St James Creation today at #EchigoTsumari_Auditorium. It was an occasion that corrects the way Echigo Tsumari Art Field is imagined (from some in Hong Kong, including artists and visitors) as related only to 'villages' as an idea of the 'rural' that is frozen in time. Instead, agriculture and commerce are involved with each other; farming communities are supported by urbanization; art emerges out of overlapping systems including processes of negotiation that recognize citizens as masters who govern what the common good is. In this case, well-being of the land gives rise to well-being of human and other beings with art being a medium that transmits - a symbiosis central to the triennale. Does the equality of freedom not have to be instituted and the care for each other be nurtured first for anything like this to happen? Not sure if it was Mars or Jupiter I was gazing at just now...but the wonder remains. (Yang Yeung)

#StJamesCreation

#Snow_of_Spring by #José_de_Guimarães

#Mars_and_Jupiter_in_July_sky

30 July 2018

Reports from Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, around #HKHouse: special immersion on #KingsleyNg_StephanieCheung's 'Twenty-Five Minutes Older' accompanied by a booklet cuddled by light and shadows...grew 5 minutes younger. http://www.echigo-tsumari.jp/…/ar…/twenty_five_minutes_older(Yang Yeung)

Reports from Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, around #HKHouse: special immersion on #KingsleyNg_StephanieCheung's 'Twenty-Five Minutes Older' accompanied by a booklet cuddled by light and shadows...grew 5 minutes younger. http://www.echigo-tsumari.jp/…/ar…/twenty_five_minutes_older(Yang Yeung)

29 July 2018

Reports from Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, around #HKHouse: No picture for any of this except the circumstances (what's around) - to You who gave the warmest smiles, to You who speak no Cantonese the way I speak no Japanese, to You who brings the touch of sun on skin to the gazbacho Herman and Pak made, to You who say 'I'm happy' the way I too say 'I'm happy', to You who is so needy of sleep but still stand....Resentment or gratitude? It's a choice not entirely up to us, but also up to us. What makes a day long? Is 'long' too much? Is 'long' a measure? Is 'long' bountiful? Is 'long' a stretch of time? Is 'long' all of the above, or everything beyond the above? Inspired by books in the open shelves of #Kinare_Tokamachi...(Yang Yeung)

28 July 2018

Reports from Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, around #HKHouse: volunteered for artist #Shimabuku to plant flowers in the fields around Ketto village in #Akiyamago. He has other works there, including one that gets cucumbers to 'fly' (being transported) above rice fields using a pulley system mounted on old wooden towers on both sides. 'It used to be rice flying; now it's cucumber or tomato,' he said. 'Why here?' I asked. 'Here, no one has time to get fat. They are always working the fields. I'm curious why people chose to live here. They are different from city people.' 'Perhaps spiritual, perhaps to be close to nature,' I said. 'Yes, but nature is also very harsh. Maybe, to hide...' I think of how everyone needs to hide sometimes - artists, farmers, hunters the like; then, all of a sudden, nature wakes us all up from it, neither for good nor bad; just to be. Next to the artist's work is a tree trunk with claw marks of a bear. The artist said the bear is nicknamed #crescent_bear' because of the patch of white fur on its chest. Nearby, #JunHonma's #MeltingWall outside a school-turned-onsen. From a turquoise blue, the 'wall' returned water to the summer sky. (Yang Yeung)

27 July 2018

Reports from Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, around #HKHouse: full moon tonight; first rim, second rim, third rim, infinitely pushing out its own coordinates until they are invisible to the human eye. Thinking of another way to regard the so-called 'white cube' gallery: the 'white' is a blandness and blankness that some art needs, to seek infinite expanse... (Yang Yeung)

中文

中文